At the end of March 2022, the third and last of a total of three exceptional CDs was released on the Schweizer Fonogramm music label: The world premiere recording of the six-part symphonic work by Swiss composer Joseph Lauber, rediscovered by Swiss conductor Kaspar Zehnder in 2017. Lauber was a well-known Swiss musician in his time – from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century – whose work left a distinctive mark first in the Neuchâtel region, then in the Zurich area and, from 1900, especially in Geneva.

Read Kaspar Zehnder’s thoughts on this in the interview with Angela Kreis-Muzzulini.

AKM: Kaspar Zehnder, both in your capacity as a conductor and as a flutist, you are known for always discovering new things. How do you find unknown, unusual musical works?

I think you just have to go through the world and through life with open eyes and ears, then things fly at you. Then you have to be critical enough to separate what is interesting for the current moment from what is irrelevant. Joseph Lauber was brought to my attention by my wife, the flautist Ana Oltean, who grew up nota bene in Romania. Lauber significantly expanded the repertoire for flute at a time when it had only just awoken from a long slumber as a solo or chamber music instrument. I then did some research on the internet but found little about Lauber, the most important being a reference to a catalogue of works published by the Lausanne University Library. This green Lauber bible is my key to the treasure chest, still is.

What role does Swiss music play in your research and in your programming?

As a guest conductor of foreign orchestras, I am always asked if I could put together a concert programme that makes reference to Switzerland as an Alpine country. While working on the programme for the “Swiss Spring”, a series of events in the Czech Republic that I had the privilege of curating in 2013, I began to look at Swiss music beyond the Arthur Honegger or Frank Martin who are still known abroad or the contemporary composers who are still alive.

What exactly do you mean by contemporary composers? Is there a difference between them and composers of today?

The terminology is broad: Current music, contemporary music, modern music. Fortunately, people have become a bit more tolerant today and let composers have their own aesthetics or judge the quality rather than the absolute and unconditionally new. I have always had great difficulty with the contemporary dogmas of the 20th century and a great understanding for dissidents and eccentrics, because they ultimately helped contemporary music out of its impasse. Again: it is much more important to compose with imagination and with the courage to be independent than to strive only for Darmstadt regulations or the cachet of French post-war aesthetics.

What is the secret of the success that you repeatedly experience with performers and audiences with newly discovered works?

Since taking up my position in Biel/Solothurn, in addition to regularly cultivating the music of composers still living in our country, I have repeatedly encouraged international soloists to play works by Swiss composers who were very much played in their day but are now almost completely forgotten: Juon, d’Alessandro, Burkhard, Schibler, Moeschinger or Beck, for example, each time with great success among performers and audiences.

Do you obviously pay special attention to Swiss composers?

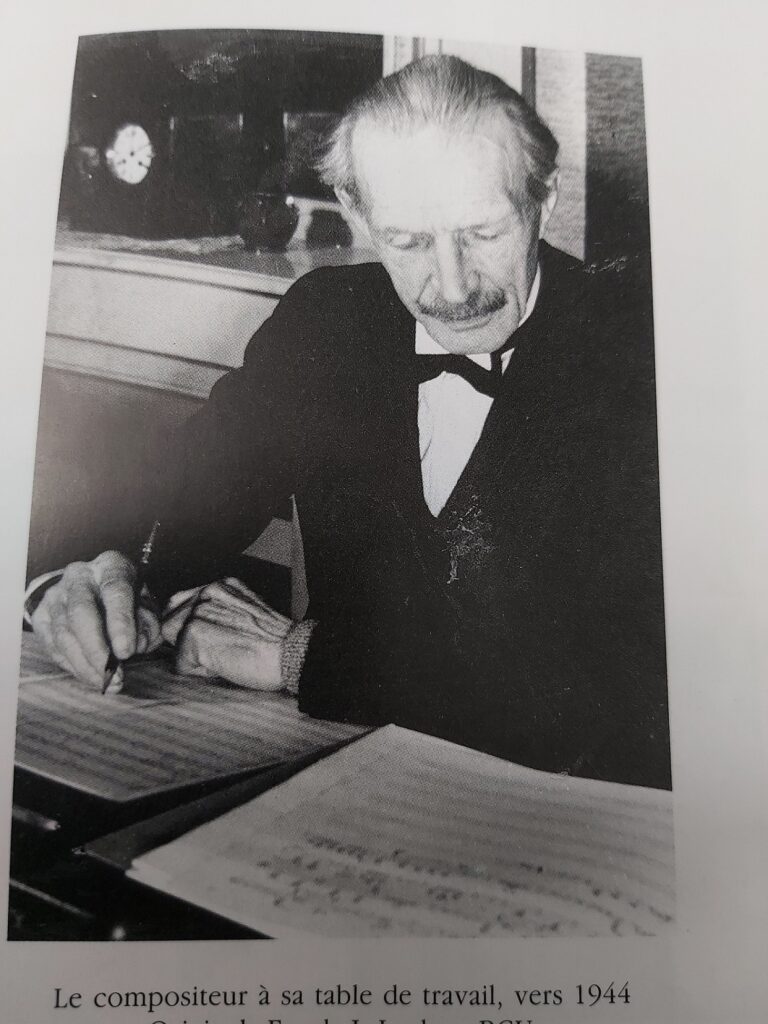

In the 2016 edition of my Murten Classics festival, the theme was “La Suisse”, 35 concerts revolved around music written by Swiss people or in Switzerland. Among the discoveries, the most important was probably the flute concerto by Joseph Lauber. It had lain dormant for decades; I played it from the original material of the premiere. Lauber’s fluid, generous handwriting inspired me a lot when I was practising.

Did you anticipate such a richness in Lauber’s work?

I was very surprised when I came across the abundance and variety of his work in the catalogue of his works. Of course, I first wanted to find out about the biography of the Geneva pedagogue (as is well known, he was the teacher of several Swiss composers such as Frank Martin, Richard Flury, Henri Gagnebin, André-François Marescotti or Emil Frey), but I could find very little information.

Joseph Laubers works have accompanied you for a long time. How did you feel when you were able to play his six symphonies, which you had rediscovered, with the orchestra for the first time?

There were five moments throughout that time that I will always remember with chicken skin:

1. in February 2018 – the first sighting of the six symphonies from the boxes in the Lausanne library.

2. two years later – the first rehearsal of the First Symphony for the test ABO concert in February 2020.

3. end of May 2020, immediately after the first Corona lockdown: the first reunion with parts of the orchestra for the preparations of the recording.

4. during the summer holidays in 2020: the moment when I got the first cut and could listen to it in my living room.

5. in April 2022, when I held the three CDs completed in my hands.

What is significant in the world of Swiss music at the turn of the century 1900?

Even if much is incomplete and awaits further scholarly investigation, Joseph Lauber’s curriculum vitae contains many clues that are significant for Swiss music around 1900:

Lauber was equally at home in German-speaking and French-speaking Switzerland. He personally witnessed the founding of conservatories, concert halls and opera houses and fused the impressions of German late Romanticism and French Impressionism gathered during his education with his own inspiration. It is immediately clear from the introduction to his First Symphony: this is the sound of the Alps. And as a founding member of the Swiss Tonkünstlerverein, he expressed his ambition to define an independent Swiss national music that transcended language barriers.

How can it be explained that composers like Johann Sebastian Bach or Joseph Lauber are forgotten?

Joseph Lauber had the good fortune to be part of the great music-historical currents in the late 19th century, but he also had the bad luck to be overrun and displaced by the wave of the musical avant-garde after the first half of the 20th century. Only this, and not a lack of quality in his work, can explain why Joseph Lauber remained forgotten until recently, why none of his orchestral works appear in the programmes of orchestras in Switzerland or abroad.

With the greatest artistic conviction, the sound engineer Frédéric Angleraux, the Sinfonie Orchester Biel Solothurn, the label Schweizer Fonogramm, the music publisher BIM and I have set out to close this gap.

Joseph Lauber

was born in 1864 in Ruswil, Lucerne, grew up in the Neuchâtel Jura, played in his family’s chapel as a child, was encouraged by an important chocolatier and sent to Zurich to study music. In Zurich, Friedrich Hegar (director of the Tonhalle, conductor at the city theatre, choirmaster, founder and director of the conservatory) was his patron. After Zurich, Lauber’s other stations were Munich, where as a pupil of Joseph Rheinberger he met later important exponents of German late Romanticism, Paris, where he experienced the emergence of musical Impressionism at first hand in the care of Jules Massenet. Back in Zurich, he led a piano virtuoso class and was a founding member of the Schweizerischer Tonkünstlerverein. The latter was founded in an effort to give Swiss music an intercantonal (national) and international reputation. Around the turn of the century, Lauber followed an appointment to the Geneva Grand Théâtre, where he conducted numerous operas (by Massenet or Puccini, for example) in their Swiss premieres; later he was a teacher at the Conservatoire de Genève. In the summer months, he retired to his chalet in Les Plans s. Bex and, until his death in 1952, composed a wealth of works inspired by the vast alpine landscape Music inspired by the vast alpine landscape, which today are once again attracting international attention for their diversity of ideas and creativity.